30

Las Vegas. Unseen by most outside Maryland’s maritime commun-

ity — sitting west of Fort McHenry — is Locust Point’s marine termi-

nal, one of the largest sea and rail complexes ever built, a grain and

coal colossus instrumental in putting Baltimore on the world map.

Garrett’s empire-building strategy — driven by his determi-

nation to maximize the Port’s yield — had a profound impact on

Maryland’s economy.

First there was the rolling stock: Just between 1848 and 1851,

Mt. Clare turned out 190 locomotives alone. Hundreds of railroad

bridges needed to be built; Wendel Bollman, after working as

an engineer for B&O, developed America’s first cast-iron bridge.

Shops, offices, rail stations and operational buildings were con-

structed, which necessitated street improvements and more

employee housing. Finally, supplier and support industries were

also required. All of this activity created demand for brick and

iron, for engineers and architects, and general labor.

The B&O was not the only game in town. At the same time the

Western Maryland was developing, the Northern Central Railroad,

controlled by the Pennsylvania Railroad, also began, while the

Canton Company, through Alexander Brown and Co., had built

the Union Railroad.

Of course, this competitive frenzy of railroad-building was

driven by the presence and commercial appeal of the Port, and

the inevitable sequel was the railroads’ subsequent attempts to

tighten their grip on Baltimore’s maritime commerce through

increased investment and construction of massive marine ter-

minals, which provided thousands of new jobs and intensified the

Port’s multiplier effect on Maryland’s economy.

The Port’s rail rivalry had indirect benefits, opening up places

such as Ocean City in Worcester County on the Eastern Shore.

For years, its trickle of visitors had to hire small boats to cross

Sinepuxent Bay until it was bridged by a rail trestle in 1876. By

1891, Baltimoreans could reach the resort just six hours after

boarding a departing steamer at Light Street.

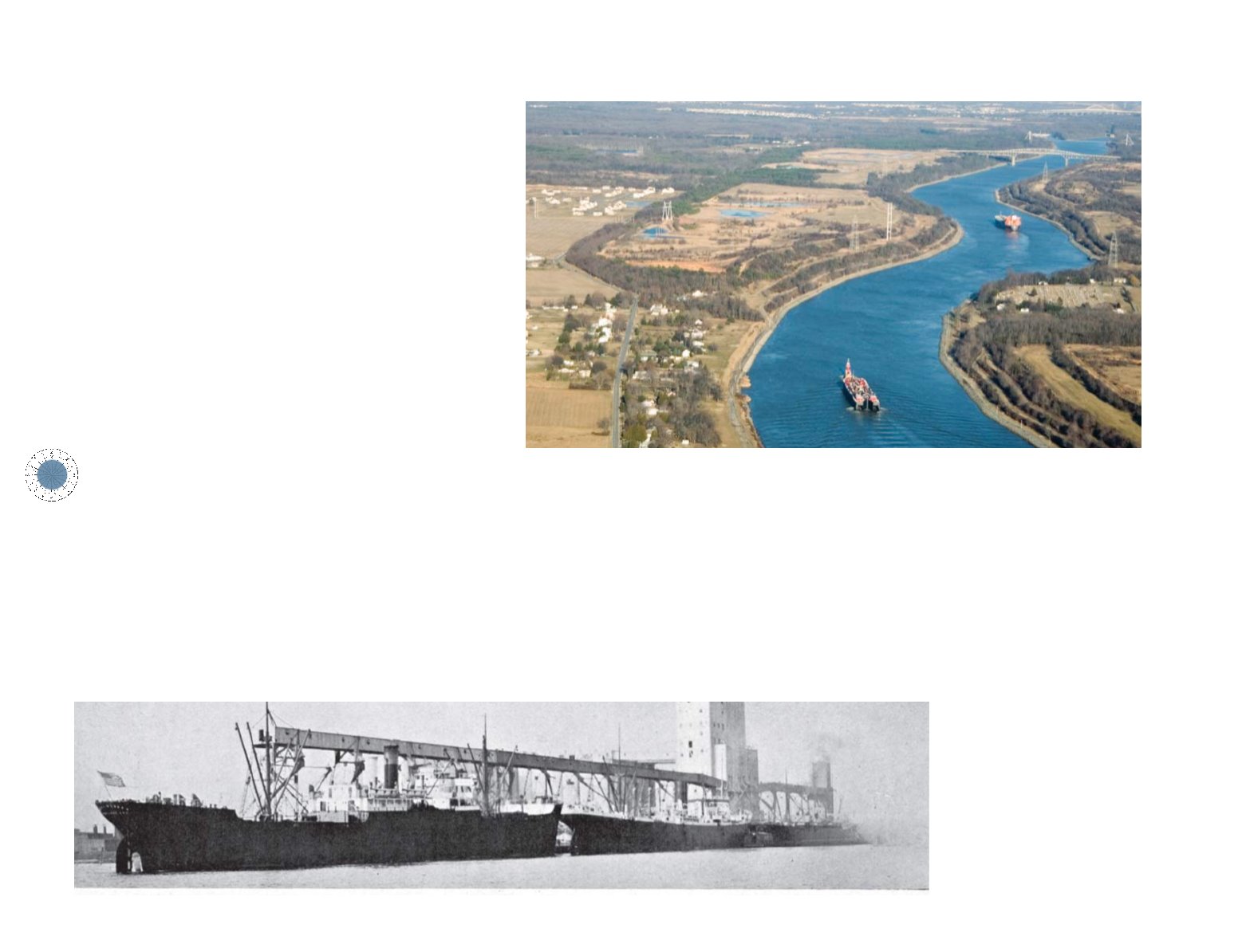

The Port acquired a second access route to international

sea lanes with the completion of the 14-mile Chesapeake and

Delaware Canal in 1829, a real time-saver for deepwater North

Atlantic traffic or northern East Coast ports.

Above: A ship navigates the

Chesapeake and Delaware

Canal, trailed by an oil barge

under tow. The canal connects

the Port of Baltimore with

Philadelphia’s oil refineries

and cargo facilities.

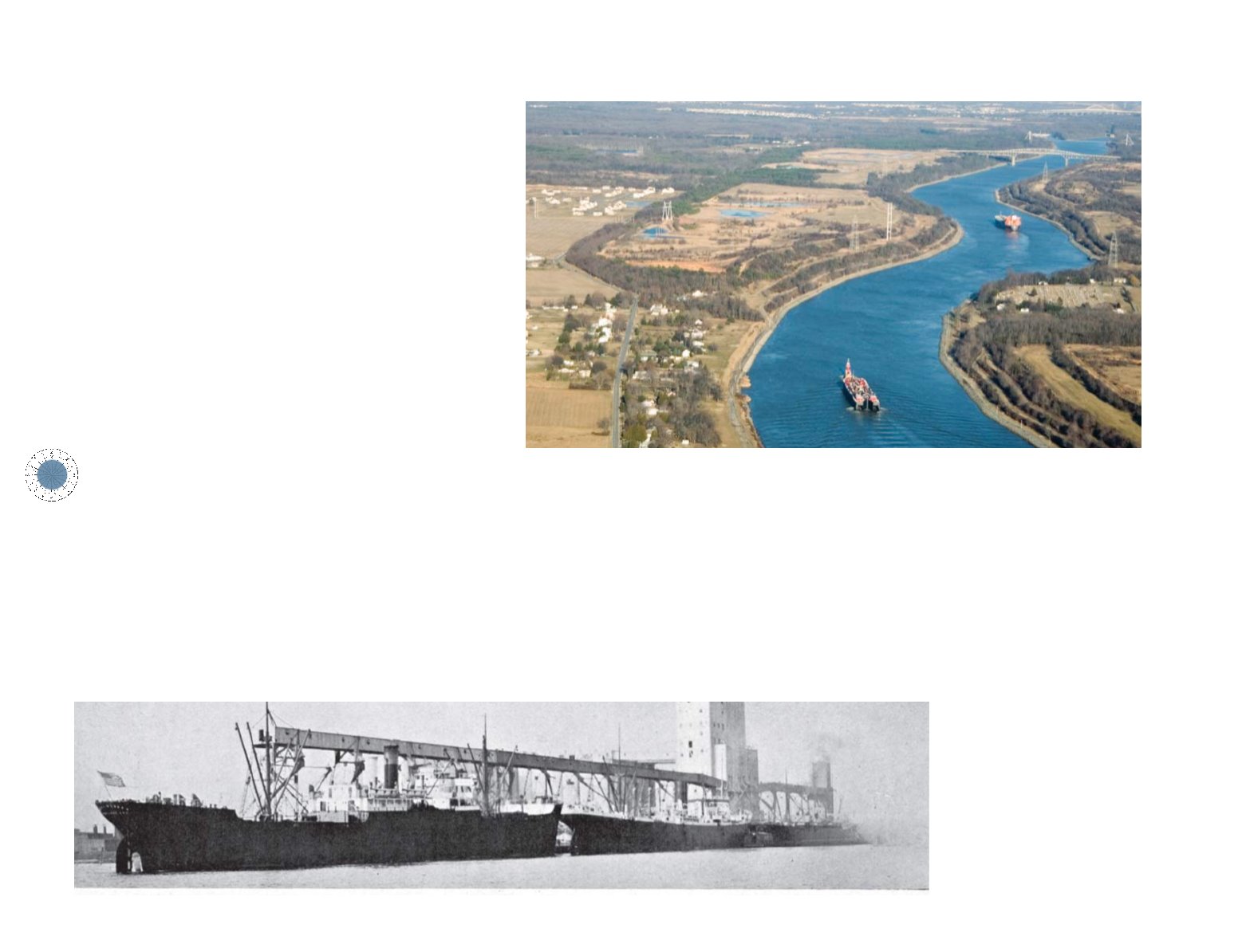

Left: Two American-flag

steamships are loaded with

grain in 1929 at theWestern

Maryland Railroad pier at

Port Covington.